“The Incurable Egoist” was the first showing of photography by Masahisa Fukase in seven years since 2008’s “The Solitude of Ravens” at Rat Hole Gallery. Through this exhibition, I strove to give visitors an overview of Masahisa Fukase’s creative efforts as a photographer, from his earliest works such as “Slaughter” (1963) to his final projects “Private Scenes” and “Bukubuku” (both 1991).

Masahisa Fukase passed away in 2012 at the age of 78. Though his artistic career spanned just 30 years from his first show “Seiyujo no Sora (Sky of the Refinery)” in 1960 to his final exhibition, “Private Scenes ’92,” in that short time he produced masterpieces such as “Yoko,” “Ravens,” “Sasuke,” “Family,” and “Private Scenes” More than individual creations, each of these projects represent a turning point in Fukase’s life and thus can be seen as part of a single series crafted over the course of 30 years. The common feature binding them together is Fukase’s idiosyncratic, deeply subjective way in which he views the world, and this is perhaps one of the most fascinating features of his work. While most people are familiar with Fukase’s “Ravens,” this series barely scratches the surface of his oeuvre. My goal with this exhibition was to present a broader exploration of Fukase’s endeavors from a more commanding perspective.

The exhibition shares its title, “The Incurable Egoist,” with an article written about Fukase in 1973 by Yoko Wanibe (who was married to Fukase at the time) for “100 Photographers: Their Faces and Works,” a supplement for Camera Mainichi. In the article she states the following:

“We have lived together for ten years, but he has only see me inside the lens, and I believe that all the photographs of me were unquestionably photographs of himself.”

Drawing upon these words depicting the true nature of Fukase – who gazed first and foremost into himself no matter who or what was before his lens – as a point of reference, I decided to display some of his iconic works alongside rare, unpublished pieces from his decades of silence, as well as old books and magazines featuring Fukase from around that time. I will now go on to explain each section of the exhibition in detail.

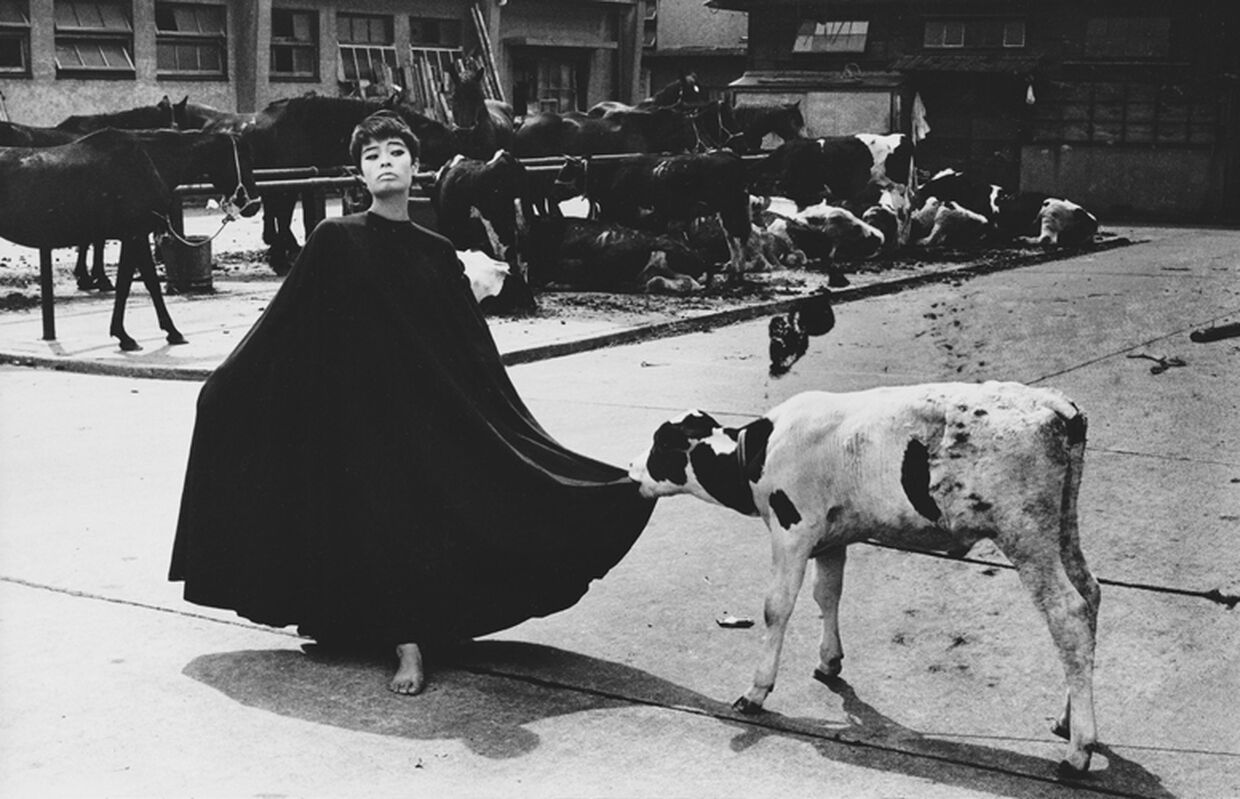

SLAUGHTER, 1963

In the summer of 1963, Fukase, then 29 years old, brought a young woman to a slaughterhouse in Shibaura. Her name was Yoko Wanibe, and she had just arrived in Tokyo from Kanazawa. As Fukase wished, Yoko wrapped herself in a black cloak and struck various poses beside the oddly shaped metal fixtures gleaming darkly with the blood and fat of the butchered animals. The photos resulted in this series entitled “Slaughter”.

This was Fukase’s third time shooting at a slaughterhouse. The first time was in preparation for his exhibition “Kill the Pigs,” while the second time was after the disappearance of his live-in partner, who vanished suddenly immediately after giving birth for unclear reasons. Yoko is the one who appeared before Fukase as he lingered in the depths of despair at having lost his lover and child.

Though she stood in a slaughterhouse thick with the stench of death and was facing Fukase’s raw desolation head-on, Yoko responded with her entire body as she moved the cape around freely. The resulting images are a symbolic representation of the opposing forces of life and death.

Fukase and Yoko were married the following year in 1964. For the next 12 years Yoko would be a centerpiece in Fukase’s photos, and this collaboration would eventually lead to “Yoko,” one of his most iconic series.

Yoko looks back on her life with Fukase and their photographic journey in the following manner: “We have lived together for ten years, but he has only see me inside the lens, and I believe that all the photographs of me were unquestionably photographs of himself.” (From the text “The Incurable Egoist” in the 1973 supplement to Camera Mainichi [100 Photographers: Their Faces and Works])

Having been dubbed “the incurable egoist” by his wife, Fukase increasingly immersed himself in the production of works of an intensely personal nature.

RAVENS: NOCTAMBULANT FLIGHT, 1980

“Ravens” is one of Fukase’s masterpieces. Though the works have been released as a black-and-white photo collection three times in the past, the first, fourth, and sixth installments of the serial feature “Ravens” in Camera Mainichi (an eight-part series that ran between 1976 and 1982) from which the pieces are derived are actually in color. This particular series entitled “Ravens: Noctambulant Flight” (the sixth installment in the magazine serial) stands out in particular due to the use of montage techniques.

Fukase was in fact a photographer who made excellent use of such montage techniques. “Metamorphosis,” his first piece to appear in Camera Mainichi (February 1962 issue), was made using layered negatives. His 4 x 5 color multiple-exposure photos also appeared in the magazine’s regular feature “Color Approach” in the same year. Similarly, he experimented with 35-millimeter multiple-exposure in the series “A PLAY” between 1970 and 1973, confirming his interest in photographic expression beyond simple documentary-style photography. However, in his explanation for “Ravens: Noctambulant Flight” he declared that, having realized his own monomaniacal tendencies and the dangerously unrestrainable nature of montages, this would be the only time he would make use of the technique.

The layering of ravens with the sun in this piece is reminiscent of the “Yatagarasu” or three-legged raven of Japanese mythology. It is perhaps easier to get a sense of the title “Noctambulant Flight” when one thinks of the Yatagarasu’s nature as an embodiment and messenger of the Sun. Fukase and Yoko, the wife who had been at the center of his work for so long, had divorced four years earlier in 1976. Afterwards, Fukase embarked on a succession of aimless travels. Perhaps he was trying to escape, hoping that the ravens he randomly turned his camera towards at one of his destinations would provide some words of guidance.

One can sense Fukase’s feeling of desolation from the blue and red skies in the background of this series.

FAMILY, 1971-1989

“Family” is one of Fukase’s best-known collections. The grand story behind it began in 1971 when he returned to his hometown of Bifuka in Hokkaido for the first time in many years with Yoko.

Fukase was born into a photo studio, and was supposed to take over the family business for the third generation. But after graduating from college he met a girl, leading him to find work in Tokyo. In Fukase’s words: “That was the crossroads where I chose to become a photographer rather than to take photos in a photography studio.” He would later spend the next dozen or so years completely uninterested in his hometown. However, upon reaching his mid-thirties Fukase suddenly began to miss the place of his birth, and from 1971 he returned repeatedly. Bifuka, his father, and the rest of his family started to appear in his photos.

“The old Anthony camera we used to use was still in good health up in the second floor studio. So, I took a commemorative photo with everyone. At the time, I was into pretentious setups, and wasn’t thrilled with the idea of simply taking a shot of everyone together. So I decided to spice things up by adding a nude in a loincloth.” (Family, IPC, 1991)

Just as he explains, one of the family portraits from 1971 shows Yoko, who accompanied him from Tokyo, wearing nothing but a loincloth.

Though the series started half as a joke, it continued almost yearly up until 1975. After that, there was a 10-year blank period during which Fukase “grew bored of doing the same things in the same place, and wanted to focus on other themes in Hokkaido.” However, when he decided to try again in 1985, Fukase noticed that his father had aged drastically, and realized that he wouldn’t be around much longer, prompting him to resume the series. His father would pass away in 1987, with his elderly mother’s death in 1989 putting a final close to the series.

“Family” began as a light-hearted parody captured on film which, over the course of 20 years, turned into a photographic record of an unexpected conclusion: the closing of a photo studio that had been in the family for three generations, and a dispersal of the once close-knit family members. Now, these photographs are the only place in which the Fukase family will forever be together.

PRIVATE SCENES, 1990-1991

“Private Scenes” is one of the works that Fukase created for “Private Scenes ‘92” (Nikon Salon, 1992), the last exhibition that he would oversee himself. The technique of inserting himself in the frame is similar to the “selfies” we see today. Some images in the series appear to have an almost humorous intent, but there are also some in which he seems to be playing with sensory or compositional elements of the shot. Regardless, for a photographer like Fukase who focused so intently on himself up to this point, it seems that these shots of himself were not merely meant to be self-portraits.

“What I am interested in is always myself, and how my own senses have reacted to social phenomena I have witnessed. For the past three years or so, I have included myself in all of the photographs I have taken. I did not intend these as self-portraits, but my interest was in the relationship, or the sense of distance, between me and the phenomena I was photographing.” (Aperture 129, 40th Anniversary issue, Fall 1992)

Until then, Fukase had been fixated on the idea of depicting himself through others.

“I kept dragging loved ones into my work in the name of photography, but I never could make anybody happy that way – not even myself. I wonder whether I’m truly enjoying myself when I take photographs?”(Camera Mainichi, January 1975 issue)

As the quote indicates, Fukase looked back on his past with some regret and loneliness. However, we can also see that by turning the camera on himself, he discovered a reciprocal nature in what had been a previously one-sided relationship with photography, and thus found a new way of playing with his craft. The sheer number of self-portraits that he took in the latter part of his career attests to this. The final destination of his intensely personal and self-absorbed photographic journey was noe other than his own image.

BUKUBUKU, 1991

“Bukubuku,” Fukase’s last collection of work along with “Private Scenes”, was also exhibited in his final exhibition “Private Scenes ’92.”

Fukase brought a waterproof camera into the bathtub of his home, placed his body – then verging on 60 years of age – in front the lens, and blew bubbles. It was really quite simple, but some might also see it as a sign that he was losing his mind. However, Fukase’s act of turning his gaze – one that had so long focused on others – onto himself and then submerging himself in bathwater (perhaps representing a mother’s amniotic fluid) could be seen as a sign that the long-running chaos within him had finally stabilized.

Also evident is Fukase’s desire to simply have fun, rather than forcing himself to turn the act into another form of creative expression. It was as if he was trying to put the following verse of the twelfth-century song “The Ryojin Hisho” into practice: “We are all born to play, born to have sport. Listening to the voice of children who play, even my limbs are stirred.” Fukase left the following words describing his mindset at the time.

“For the past four years or so, I’ve put myself in every image I’ve taken. It’s verging on a sickness, almost to the point where I feel like I’ve got eyes on my back. While I’m undoubtedly the subject of these photos, I enjoy playing with the distance between myself and what’s behind me. So while I may occasionally think the image would be better off without my face in it, I can’t stop, even though I know better.” (Nihon Camera, March 1992 issue)

Fukase was never truly able to enjoy the period in which his gaze was directed at others. With the lens now pointed at himself, he finally found heartfelt enjoyment in photography. At the same time, he had been unconsciously working on what would be his final creations as an artist.

CATS, 1974-90

Cats simultaneously captivated Fukase above all else, and were a subject that he frequently projected himself upon. Their lack of ability to understand language perhaps made it easier for him to deal with them in an unaffected manner. He left behind many pictures of felines.

“They say that cats are terribly nearsighted yet hear extremely well, since they are so low to the ground. I spent much of the past year shooting photos while lying on my stomach at what would be eye-level for a cat, to the extent that I felt as if I had become one myself. Taking photos and playing with whatever struck my fancy throughout the changing seasons was an enjoyable way to work. I had no interest in taking photos of cats that looked beautiful or cute; rather, I wanted to capture the endearing image of cats with my own image reflected in their eyes.That’s why this collection could be described as a ‘self-portrait’ in the disguise of Sasuke and Momoe.” (The Cats’ Straw Hats, Bunka Publishing Bureau, 1979)

Fukase wrote that he had an unbreakable bond with cats from as far back as he could remember, so it’s no surprise that he had many of them as pets. There was Tama, the tortoiseshell he had from the time he was a young child up until high school, Kuro during his days in college, and then Hebo and Kabo, a black Persian and Siamese respectively, that he had while living with Yoko in Matsubaradanchi. Then there were Sasuke the First, Sasuke the Second, and Momoe, the mixed-breeds featured across three photo collections. During the ‘90s he had Gure, a Russian blue. Hebo and Kabo, who Fukase and Yoko each doted on during their days in Matsubaradanchi, mainly appeared here and there in magazine features without ever getting the chance to appear properly in photo collections. Still, their relaxed camaraderie and comical faces display a charm different than that of Sasuke and Momoe.

Here we have a selection of shots featuring the friendly duo of Hebo and Kabo, along with the playful Sasuke, and Gure.

Putting “The Incurable Egoist” Together

“The Incurable Egoist” was a huge success, with many visitors coming to see the show. This exhibit is the first project of The Masahisa Fukase Archives, an organization founded in the hopes of conveying the accomplishments of Masahisa Fukase to the world, so we are very grateful to have achieved such a fruitful result from the beginning.

How can we present the work of an artist who is no longer with us? This has proven to be a crucial question not just for this exhibition, but also for all activities promoting the work of deceased creators. As a member of The Masahisa Fukase Archives and the curator of this exhibition, my intention was not to simply arrange Fukase’s photographs on the walls of some white cube, but rather to depict a journey that follows the subjects he explored during his life.

What did this man feel, gain, and occasionally suffer as he confronted photography, his subjects, and himself? What kind of facial expressions did he make, and how did he think? My desire was to put together a photographic journey that would allow us to come face-to-face with Masahisa Fukase the man. By doing so, we would be able to connect the dots and gain a sense of chronology over the course of Fukase’s 30-year career.

This is why I decided to place a large portrait of Fukase in the center of the venue, why all of the works on display were linked together along a single path, and why it was essential that we have a corner where guests could peruse books related to Fukase at their leisure.

In particular, there was a behind-the-scenes miracle involved in completing the wall with Fukase’s portrait on it.

The portrait originally appeared alongside the original “Incurable Egoist” article written by Fukase’s aforementioned ex-wife Yoko. But after searching and searching, we were still unable to find the negative of the picture. We unearthed tiny prints of the portrait, but they were far too small to enlarge for a wall of that scale. The portrait was shot by Kazuoki Nozawa, a photographer who once worked as Fukase’s assistant. We attempted to contact Mr. Nozawa through an acquaintance of his, but apparently he had passed away just a few weeks prior.

I had sworn that I wouldn’t give up until the bitter end, but needless to say, I was devastated by the news. I immediately began thinking of an alternative idea that we could use in lieu of the portrait, but I still wasn’t ready to throw in the towel quite yet. Finally, by a stroke of luck I managed to contact Mr. Nozawa’s family, who were kind enough to send me the negatives from the remote location of his home. All of this happened not even a week before the opening of the exhibition.

Many of the other pieces meant to go on display were also sitting in various states of disarray. I spent a year working in tandem with Yoko, digging up negatives, organizing prints, and so on in a process not unlike putting together a complex jigsaw puzzle. At times we jumped together in joy, and other times we butted heads over different interpretations of certain works, but either way we somehow managed to finish everything before the date of the show. Perhaps “miracle” sounds like a bit of an exaggeration, but it was thanks to many instances of near-miracles that this exhibition came together. Each time we experienced one such miracle, a feeling of reassurance would wash over me, as if Fukase himself was there with us. But more importantly, this exhibition would never been possible without the cooperation of many people, so I would like to take a moment here to express my deepest gratitude to the family of Mr. Nozawa and everyone else who helped along the way.

The books on hand in the venue were various photo books and magazines that I had picked up in the 15 years since I first found out about Fukase. While there is no doubt about the caliber of his work, breathing life back into art that has been gathering dust for some twenty-odd years is no easy feat. In particular, many young people are not familiar with Fukase, so it was like we were starting from scratch as we tried to spread word about him. These books – artifacts from an era when Fukase was still alive – speak volumes in helping such viewers understand the context of the artist’s work.

The books were absolutely essential to the exhibition in my mind. My conviction was especially reinforced by the memory of being blown away at the age of 18 when I first beheld “Ravens: Noctambulant Flight” upon opening the March 1980 issue of Camera Mainichi 15 years ago. It had been thirty years after the series was originally released, yet as a teenager I was able to thoroughly enjoy Fukase’s work with such freshness, partly because I was introduced to it through a magazine – a medium that hinges on timeliness and a feeling of the “new.” So I decided to wager upon those experiences in this exhibition with the confidence that even the youth of today would find Fukase’s work fresh and compelling, as long as they were introduced to it in the right way.

Some of the books meant to go on display were quite rare, so I did have some initial concerns that they might become tattered over the long course of the exhibition. However, thankfully all the attendees were very cooperative, and the books remained in great condition despite over two months of browsing. I plan on exhibiting them again someday at future Fukase exhibitions.

This exhibition “The Incurable Egoist” was a journey into the soul of Masahisa Fukase. My greatest hope is that everyone who viewed the exhibition took away something different. The Masahisa Fukase Archives will continue to show the works of Fukase for the enjoyment of the world. Please look forward to our upcoming projects.